Alexander the Great in Christianity and Islam, Part One: The Christian Tradition

Fourteenth-century Byzantine miniature from the Alexander Romance. Here Jewish religious leaders are shown presenting gold to Alexander the Great (Image credit: Wikimedia Commons)

NOTE: For those interested in Alexander’s place in the Islamic tradition, click here to read Part 2.

While Alexander the Great’s exalted status in modern-day Greece and elsewhere in the Balkans may be attributed in no small part to both the revival of Hellenism during the Greek Revolution and to other regional movements for national independence and ethnic identity in lands formerly ruled by the Ottoman Empire, his legacy was far from forgotten in Byzantium. And how could it have been? Not only was Byzantium a Greek-speaking empire that encompassed Greece and many of the other lands that had once been ruled by the Macedonian king, but the Bible itself speaks of Alexander, with the first of two scriptural references to him being found in the rather prominent Book of Daniel.

The Book of Daniel is set during the Babylonian Captivity in the sixth century BC and is centred around the apocalyptic visions of its namesake, the Prophet Daniel. Interestingly, though Daniel is regarded as a prophet in Christianity, and usually in Islam as well, he is not in Judaism. While Jews accept the canonicity of the Book of Daniel, and even revere the man himself, it seems that he missed the cut-off date for prophethood in Judaism, as the office of prophet is said to have ended with Malachi. Moreover, despite the Book of Daniel’s sixth century BC setting, scholars tend to agree that it was likely composed four centuries later. Nevertheless, since Alexander lived during the fourth century BC and the Book of Daniel is set two centuries before then, the text speaks of him in a prophetic manner. We read of how Daniel is given a vision of a ram and a goat:

As I was watching, a male goat appeared from the west, coming across the face of the whole earth without touching the ground. The goat had a horn between its eyes. It came toward the ram with the two horns that I had seen standing beside the river, and it ran at it with savage force. I saw it approaching the ram. It was enraged against it and struck the ram, breaking its two horns. The ram did not have power to withstand it; it threw the ram down to the ground and trampled upon it, and there was no one who could rescue the ram from its power. Then the male goat grew exceedingly great; but at the height of its power, the great horn was broken, and in its place there came up four prominent horns toward the four winds of heaven (Dan. 8:5-8).

Now don’t fret if the above is not clear to you because even Daniel needed help making heads or tails of it. In fact, the Archangel Gabriel himself had to appear to the prophet in order to explain the vision:

As for the ram that you saw with the two horns, these are the kings of Media and Persia. The male goat is the king of Greece, and the great horn between its eyes is the first king. As for the horn that was broken, in place of which four others arose, four kingdoms shall arise from his nation, but not with his power (Dan. 8:20-2).

It is interesting to note the use of horned animals in Daniel’s vision. While in the biblical account, Alexander is symbolized by the goat who defeats the ram, the Macedonian king has often been depicted on coins, statues, and reliefs as having not the horns of a goat, but those of a ram. For it is said that when Alexander consulted the oracle of Ammon (Amu) in Siwa, he was informed that he was none other than the son of the ram-headed Egyptian deity himself. Thus, Alexander would soon start marketing himself as the divine offspring of Zeus-Ammon—something which helped earn him greater respect in places like Egypt, but seemingly got him a lot of clandestine eyerolls in his home country of Greece. Moreover, as we will see in Part Two, Alexander’s horns will play a critical role in potentially identifying him as the Qurʾanic figure Dhu al-Qarnayn (He of the Two Horns).

C. 305-281 BC Greek coin depicting Alexander the Great with the horns of Zeus-Ammon (Image credit: The British Museum)

The second place where the Bible speaks of Alexander is in the introduction to the First Book of Maccabees. While 1 Maccabees is not part of the Jewish canon of scripture, it is included in the Septuagint, i.e., the Greek Old Testament. Written probably around 100 BC, 1 Maccabees tells of the great Jewish rebellion against King Antiochus IV Epiphanes and the Seleucid Empire—an empire referenced above in Daniel’s vision of the four kingdoms that the Macedonian Empire would break into. Moreover, while Alexander himself is even portrayed by Josephus as deeply respectful of Judaism, Antiochus is remembered for persecuting the Jews and trying to eradicate their faith. In fact, the annual Jewish festival of Hannukah, whose origins are recounted in 1 Maccabees 4:36-59, commemorates the Maccabee rebellion against the tyrannical Seleucid ruler, and the rededication of the Temple of Jerusalem.

But what does 1 Maccabees have to say about Alexander himself? Well, it attempts to contextualize the Seleucid Empire’s control of the Holy Land by tracing the foreign occupiers’ origins back to Alexander. Thus, before ever mentioning Antiochus, 1 Maccabees states,

After Alexander son of Philip, the Macedonian, who came from the land of Kittim, had defeated King Darius of the Persians and the Medes, he succeeded him as king. (He had previously become king of Greece.) He fought many battles, conquered strongholds, and slaughtered the kings of the earth. He advanced to the ends of the earth and plundered many nations. When the earth became quiet before him, he was exalted, and his heart was lifted up. He gathered a very strong army and ruled over countries, nations, and princes, and they paid him tribute.

After this he fell sick and perceived that he was dying. So, he summoned his most honored officers, who had been brought up with him from youth, and divided his kingdom among them while he was still alive. And after Alexander had reigned twelve years, he died. Then his officers began to rule, each in his own place. They all put on crowns after his death, and so did their descendants after them for many years, and they caused many evils on the earth (1:1-9).

Although the passage is mistaken in its claim that Alexander divided his empire up while still alive—the reality being that he failed to designate a clear heir, causing the Macedonian Empire to almost immediately be thrown into chaos and civil war upon his untimely death—it still nicely sets the stage for the entrance of the book’s central villain, Antiochus.

It is also important to keep in mind that the translation of the Septuagint itself was the result of Alexander’s dissemination of the Greek language and culture throughout Western Asia. According to Jewish tradition, the Septuagint was the work of seventy (or seventy-two) Jewish scholars from the twelve tribes of Israel who were able to seamlessly translate the Hebrew Bible into koine Greek. In fact, it is said that this great undertaking was done at the behest of the pharaoh of Egypt Ptolemy II Philadelphus, the son and successor of Alexander’s general Ptolemy I Soter, who wanted a Greek translation of the Old Testament for the Library of Alexandria. There is even a hagiographical legend found in the Orthodox Christian tradition that states that St. Simeon the God-Receiver, i.e., the just man who received the infant Jesus at the Temple (Luke 2:25-35), was one of the Jewish translators of the Septuagint, and that God allowed him to live over three and a half centuries in order to witness the fulfillment of the Book of Isaiah’s prophecy concerning a virgin giving birth to the Messiah.

Unlike the Old Testament, the New Testament makes no mention of Alexander—though several minor figures bear his name, and the name of his father, Philip, is even shared with one of the twelve apostles. There are, of course, clear influences from Alexander’s conquests on the New Testament. A critical one being that following in the tradition of the Septuagint, the New Testament was written not in Hebrew, Aramaic, or Latin, but in koine Greek. The reason for this is that even though Jesus himself spoke Aramaic (though I would not discount the possibility that he taught in other languages as well), the New Testament writers hoped to reach the largest possible audience and, therefore, composed the gospels and the epistles in common Greek. Moreover, the New Testament being composed in Greek almost exclusively by Jewish converts to Christianity allowed for a powerful meeting and dialogue between the traditions of the Hebrew people with those of the Greek and Hellenized populations of the Roman Empire. Such a meeting of cultures is rather reminiscent of the spirit of Alexander himself, who had sought to blend Hellenic and eastern cultures together in order to create a new world.

The memory of the Macedonian king was also kept alive in the Byzantine Empire, and far beyond its borders, through the popularity of the Alexander Romance by Pseudo-Callisthenes in its many translations and variations. Although, as its name suggests, the Alexander Romance is not a fact-driven account of the conqueror’s life, but rather a series of fantastical tales, the original Greek version, completed in the third century AD, still does portray Alexander as having been a pagan. However, under the influence of Christian piety, later Byzantine and Syriac versions sought to present Alexander as having been faithful to the one God of Abraham. Moreover, as we will see in Part Two, a work often treated as an appendix to the Alexander Romance, but is actually an independent Christian work, the Syriac Legend of Alexander, has profound parallels with what has often been interpreted by Muslims and non-Muslims as the Qurʾanic portrayal of Alexander as a servant of God.

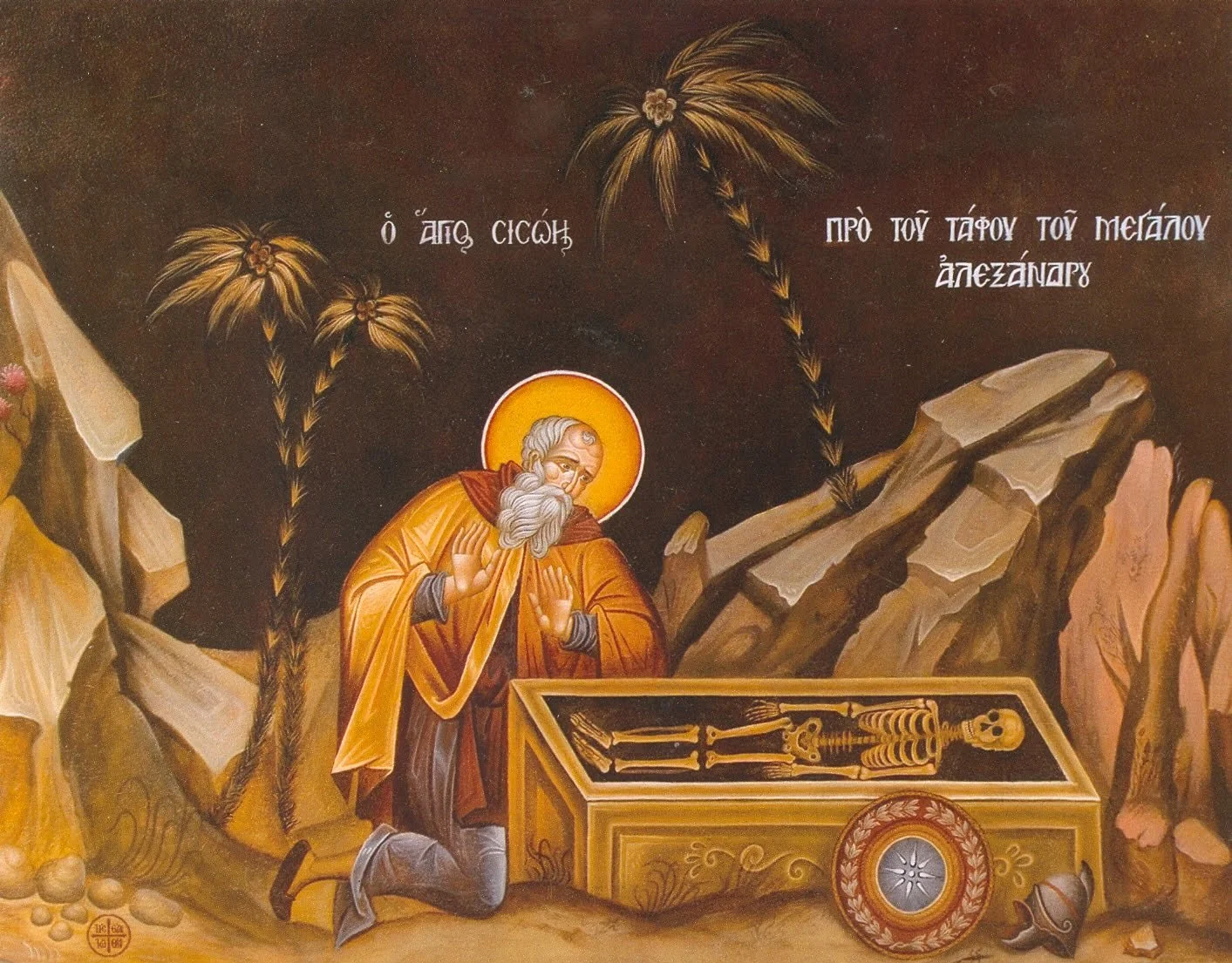

The famous tomb of Alexander is also referenced in the Christian tradition. Of course, knowledge of the location of the tomb has been lost for many centuries now. Even back in the third or fourth century AD, when contrasting the transitory nature of Alexander and his conquests with the lasting glory of Jesus and his saints, St. John Chrysostom remarked that not even the famous conqueror’s own people (likely a reference to pagans) still knew the location of his resting place. Nevertheless, Alexander’s tomb would eventually find its way into the Orthodox Church’s iconographic tradition, specifically in connection with the fifth-century desert father St. Sisoes the Great.

Greek Orthodox icon of St. Sisoes the Great lamenting at the tomb of Alexander the Great (Image credit: La Vida presente)

In these icons—which seem to have only begun to appear after the Fall of Constantinople in 1453 and can be found on church walls on Meteora, Mount Athos, and elsewhere—we see Sisoes depicted as lamenting over the bones of Alexander. This has led many a pious Orthodox Christian to believe that the icon intends to communicate a historical event, wherein the great ascetic must have visited, or perhaps even rediscovered, Alexander’s tomb somewhere in Egypt. However, that is an unlikely scenario. The purpose of this particular icon has always been to remind the believer of the tragedy of the human condition by showing that even the greatest of people are subject to death—a theme associated with the Macedonian king in some Byzantine versions of the Alexander Romance—and that authentic hope can only be found in the resurrected Christ. There may also be a bit of a play on the title of “the Great” here. Whereas Alexander received the epithet because of his worldly glory, Sisoes earned it because of his simple and humble devotion to God.

Interestingly, though many archeologists continue to search for Alexander’s tomb, one author, Andrew Michael Chugg, feels that the body of Alexander has probably already been found. According to his theory, in a potentially shocking case of mistaken identity, the body venerated as that of St. Mark the Evangelist in the famous basilica bearing his name in Venice, Italy is actually that of Alexander the Great. Chugg argues that the conqueror’s body disappeared from the historical record at the same time that two Italian merchants, who apparently wanted to preserve the relics of the apostle from the Islamic authorities of Egypt, smuggled the body in question out of Alexandria to Venice in AD 828. He further tries to buttress his theory by pointing to a discovery in the 1960s of a fragment of sculpture in the foundation of St. Mark’s Basilica that may have been part of an ancient Macedonian tomb. Nevertheless, if correct, and that remains a big if, Chugg’s theory would mean that Christians have been unwittingly venerating Alexander’s relics for centuries—I could see news of this massively increasing Greek pilgrimages to Venice as we speak.

Throughout much of the above, we see that Alexander’s legacy continued to live on both directly and indirectly in the Christian tradition. Yet, the attention paid to him never seems to have been as great (no pun intended) as it perhaps should have been. This is in part due to the fact that, despite what some Christian tales said of him later, Alexander had been a pagan who declared himself divine, and this put him at a far lower status to say the sainted monarchs of history, be it Constantine, Justinian or even a righteous Old Testament king like David. Moreover, the Greeks as a whole no longer identified as Greek but as Roman, and this meant that they did not possess the same sort of connection to Alexander that modern-day Greeks do.

Yet, near the end of the Byzantine Empire, its people began to somewhat come to the realization that their heritage was not solely that of an empire originally founded in Italy. In his essay Alexander the Great in Byzantine Tradition, AD 330-1453, Anthony Kaldellis relates that when the Turks were preparing to attack Thessaloniki in the late fourteenth century, Emperor Manuel II looked to rouse the people by stating that although they were Romans, their country could still be traced back to Philip and Alexander, and that they possessed qualities from both lines. Of course, things have changed a lot. I mean, to get a Greek now, whether a devout Orthodox Christian or not, to stop talking about their glorious descent from Alexander and the ancient Greek civilization would be a feat of strength that not even Heracles could accomplish.

Now that you have survived reading Part One, consider checking out Part Two, where I discuss the place of Alexander the Great in the Islamic tradition. For the Macedonian’s position in Islam far surpasses that of his place in Christianity, as it is arguable that even the Qurʾan itself portrays him as a person of great sanctity.