God is Not “the Third of Three”: Does the Qurʾan Accuse Orthodox Christians of Believing in Three Gods?

15th-century Russian Orthodox icon of the Holy Trinity by St. Andrei Rublev (Image credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Although the Qurʾan recognizes Christians as believers in God (e.g., 5:69) and the closest of all people to Muslims (5:82), some passages seem to accuse them of polytheism. For instance, the Muslim scripture tells Christians, “Believe in God and His messengers, and say not ‘Three.’ Refrain! It is better for you. God is only one God” (Q 4:171). Likewise, we read, “They certainly disbelieve, those who say, ‘Truly God is the third of three,’ while there is no god save the one God” (Q 5:73). Furthermore, it is often taken for granted that such passages are referring to the orthodox Christian doctrine of the Trinity. In fact, some prominent English translations of the Qurʾan, such as that of M.A.S. Abdel Haleem, even render the Arabic word thalatha (literally, “three”) in Qurʾan 4:171 as “Trinity.” However, this may be a serious misinterpretation of the text.

In Surat al-Maʾida, we are presented with a telling dialogue between God and Jesus regarding the supposed Christian worship of three gods:

And when God said, “O Jesus son of Mary! Didst thou say unto mankind, ‘Take me and my mother as gods apart from God?’” He said, “Glory be to Thee! It is not for me to utter that to which I have no right. Had I said it, Thou wouldst surely have known it. Thou knowest what is in my self and I know not what is in Thy Self. Truly it is Thou Who knowest best the things unseen. I said naught to them save that which Thou didst command me: ‘Worship God, my Lord and your Lord’ (Q 5:116-17).

There is little hint here of the Trinitarian monotheism of orthodox, or mainstream, Christianity. Instead, God in the Qurʾan specifically asks the Messiah if he had taught others to worship him and his mother as two separate gods. It can even be said that if one were to try to reconstruct the doctrine of the Trinity based on the Qurʾan alone, they would likely conclude that it consists of three distinct deities: God, Mary, and Jesus (Father, Mother, and Son). However, orthodox Christians do not believe in three gods, nor do they believe Mary to be part of the Trinity or divine. In accordance with the Nicene Creed, Christians confess faith in one God, who is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, three hypostases in one ousia. So why then does the Qurʾan portray Christianity’s concept of God in a way that does not correspond to its doctrine?

One theory is that perhaps the Qurʾan has purposefully created a caricature of the Trinity in an attempt to show the belief as self-evidently flawed. The Muslim scripture is well aware of the fact that Christians do not actually worship three different gods but is essentially arguing that any definition of God that includes a human being is incompatible with pure monotheism, or tawhid. A good example of the Qurʾan using rhetoric in such a way can be seen in its accusation that Jews and Christians “have taken their rabbis and monks as lords apart from God” (9:31). According to a hadith quoted in Ibn Kathir’s Tafsir, the Prophet Muhammad explained the verse as follows: “They [i.e., rabbis and monks] prohibited the allowed for them, and allowed the prohibited, and they obeyed them. This is how they worshiped them.” In other words, the Muslim scripture is not saying that Jews and Christians believe their religious leaders to be divine, but that they have inappropriately equated human directives with God’s. So it is certainly possible that the Qurʾan is using a similar rhetorical approach concerning the Trinity. On the other hand, it may be argued that the Qurʾan’s target audience for its polemics against the worship of three gods was not actually orthodox Christians, but a heretical sect of Christians known as Tritheists.

In his Chronicle, Elijah of Nisibis says that a Miaphysite from Apamea named John Ascoutzanges (Muqa d-zeqa) began to spread the heresy of Tritheism in 557. The Syriac-speaking Ascoutzanges appears to have been fairly unconcerned with defining his notion of the Trinity within the confines of biblical monotheism. For he taught that each member of the Trinity possessed its own unique divine essence, or godhead. Further, in a synodical letter, St. Damian of Alexandria quotes the most prominent Tritheist thinker, John Philoponus, as having stated,

The Godhead and substance of the adorable Trinity does not exist in reality but only in the mind and reason. In this way God is viewed as one, whereas there are three substances of God; and these substances and natures are distributed according to the hypostases and thus the Father is another God, the Son another God, and the Holy Ghost another God.

Therefore, according to Philoponus, God’s oneness was merely an intellectual abstraction.

In Bodily Resurrection in the Qurʾān and Syriac Anti-Tritheist Debate, David Bertaina writes, “From the latter half of the sixth century through the early seventh century, the main Christian churches viewed Tritheism (real or imagined) as a dangerous heresy that required the propagation of anti-Tritheist literature across the eastern Mediterranean to eliminate its appeal.” He also provides a number of salient examples from Syriac anti-Tritheist literature that appear to parallel Qurʾanic polemics against the belief in three gods. For instance, in a letter to the Miaphysite monks of Arabia, St. Jacob Baradaeus and Theodore of Arabia write,

As we were informed about your correct faith and the dignity of your brotherhood’s rule, beloved by God, we inform you that we have learned that some monks have gone astray, fallen into heresy, arising on account of sin. Those ones are called Tritheists, or polytheists, and [confess] three deities and go about seeking some chaste monks and lay faithful to induce to embrace their heresy.

The letter, which was composed in 567 at the behest of the Ghassanid ruler al-Harith V ibn Jabala, or Flavius Arethas, does not mince words regarding Tritheism’s insidious nature, accusing its proponents of the egregious sin of polytheism. Similarly, Paul the Black writes in 580,

We reject those who dare to say: “The oneness of the divine substance and nature is subsequent to the constitution of its being, so that this [unity] is merely a mental image and comprehended only in the imagination.” These ones are indeed outside of our sheepfold and we reject the errors of the pagans.

It seems that for Paul, Tritheism was but a new manifestation of paganism. Moreover, some Syriac anti-Tritheist polemics sound almost as if they were lifted from the pages of the Qurʾan. For example, one Christian condemnation of Tritheism states, “Let any opponent be anathema (aḥrem) who says: ‘Three gods.’” Such a statement sounds rather akin to Qurʾan 4:171. It is also important to note that Arabic-speaking Christians prior to and during the time of Muhammad did not write in their native tongue but in Syriac. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that the parallels between Syriac anti-Tritheist literature and the Qurʾan’s polemics against the belief in three gods is due to the fact that both sources were combating the same Christian heresy.

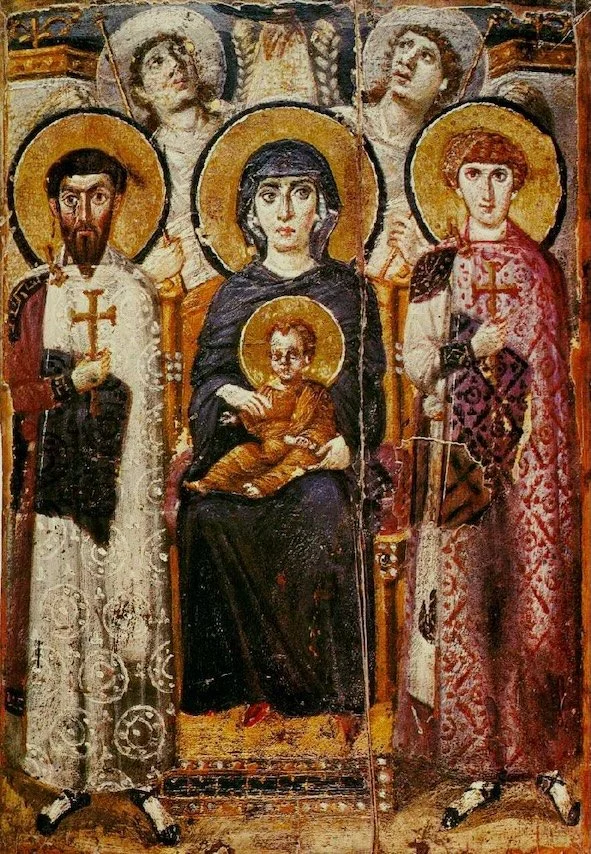

6th-century Byzantine icon of the Virgin Mary enthroned between Sts. Theodore Tiron and George. St. Catherine’s Monastery, Mount Sinai, Egypt (Image credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Of course, there still remains at least one major discrepancy between what is described in the Qurʾan and Tritheism, namely, the former’s claim that Mary was a member of a pseudo-Trinity and worshipped by Christians as a god. Like in the above-mentioned Qurʾanic polemic regarding Jews and Christians worshipping their religious leaders, it may be that the Muslim scripture is not actually claiming that Christians believe Mary to be divine but is simply saying that they have gone too far in their adoration of her. Some have argued that the Qurʾan views the Christian practice of praying to the Virgin as a form of worship. However, since virtually all Christians in the seventh century would have not only prayed to Mary but to many other saints as well, none of whom the Qurʾan accuses them of worshipping, perhaps asking for her intercession was not the issue at hand.

Instead, the Qurʾan may be criticizing the Christian Church’s designation of Mary as the Mother of God, or Theotokos (literally, “God-bearer”). If this is the case, the Muslim scripture would not have been the first to do so. Indeed, Nestorius, who briefly served as patriarch of Constantinople in the fifth century, did nearly everything in his power to prevent the Virgin from becoming known as the Mother of God, preferring instead to call her simply the Mother of Christ, or Christokos. Although his opinion on the subject would soften in time, Nestorius claimed in a letter to Pope St. Celestine that to call Mary Theotokos was to call her divine. However, the Council of Ephesus (451), as well as the pope, would agree with the Mariology and Christology of Nestorius’s opponent St. Cyril of Alexandria, who argued that Mary was truly the Mother of God because she had given birth to God incarnate, and that to claim otherwise was to deny the authenticity of the incarnation and divide Jesus into two separate persons. However, like Nestorius, the Qurʾan perhaps saw the title as exalting the Virgin beyond what is appropriate for a human being. Thus, it may have chosen to use hyperbolic language against orthodox Christian Mariology in order to expose its supposed absurdity. Yet, like in the case of Tritheism, the Qurʾan, once again, may have been responding to the heretical beliefs of a peculiar Christian sect.

In the Panarion, a fourth-century Greek heresiography, St. Epiphanius of Salamis writes about a group of women, the Collyridians, who worshipped Mary as a goddess. Supposedly, the Collyridians were initially in Thrace and northern Scythia before relocating to Arabia. Epiphanius says that their women priests ritually offered cakes in Mary’s name for all to partake in. Deeply disturbed by this, he argues that Mary was a faithful follower of God and was not given to Christians for worship. Epiphanius also references John 2:4, where Jesus addresses his mother as “woman,” as intended to protect Christians from falling into the error of worshipping her.

While the Panarion remains the only known source to explicitly mention the Collyridians, the possibility that they not only existed but were also the target of the Qurʾan’s polemics against Mariolatry should not be dismissed too quickly. Christian writers referred to pre-Islamic Arabia as Arabia haeresium ferax (“Arabia bearer of heresies”), and the Muslim scripture contains a number of references to heterodox practices within its milieu. A good example of this is its claim that Jews believe the Prophet Ezra, or ʿUzayr, to be the son of God (Q 9:30). While we do not have any other evidence for such a practice, it seems improbable that the Qurʾan invented it as some sort of bizarre polemic against Judaism. Instead, it is likely a historical reference to a group of Jews in the Hijaz that held unusual beliefs about Ezra. In a similar vein, the Qurʾan’s denunciation of Mariolatry may have been directed against a relatively obscure and heretical group of Christians (perhaps the Collyridians) in Arabia.

The Prophet’s Mosque, or al-Masjid al-Nabawi, Medina, Saudi Arabia (Image credit: Bluemangoa2s, Wikimedia Commons)

In truth, the idea that the Qurʾan accuses orthodox Christians of believing in three seperate deities is also inconsistent with other passages in the scripture. According to the Qurʾan, there is no graver sin than polytheism, or shirk (e.g., 4:48). Yet, we find a number of positive statements in the holy book regarding Christians and their faith. The Qurʾan calls Christians “People of the Book,” or ahl al-kitab, for possessing revealed scripture and counts them among those who will be rewarded by God in the hereafter (5:69). It also states, “Thou wilt find the nearest of them in affection toward those who believe [i.e., Muslims] to be those who say, ‘We are Christians.’ That is because among them are priests and monks, and because they are not arrogant” (Q 5:82). Elsewhere, the Qurʾan speaks of churches and monasteries as sacred spaces “wherein God’s Name is mentioned much” (22:40). However, if Christians were polytheists, or mushrikun, such passages would seem absurd. In fact, according to Ibn Ishaq’s Sirat Rasul Allah, while Muhammad profoundly disagreed with the Christology of a deputation of Christians visiting Medina from Najran, he still permitted them to use his own mosque, al-Masjid al-Nabawi, to perform their prayers. Of course, the Prophet, whom ʿAʾisha bint Abi Bakr called the “living Qurʾan,” would have never allowed polytheist worship to occur at Islam’s second holiest site.

While the orthodox doctrine of the Trinity is flawed according to Islam, since the Qurʾan rejects belief in Jesus’s divine sonship (e.g., 9:30), that the Muslim scripture does not seem to portray it as the belief in three separate gods is an important distinction. For it is one thing to see orthodox Christians as possessing an imperfect understanding of the one God, but an another to deem them polytheists. Moreover, that the Qurʾan appears to target the heresy of Tritheism (and maybe also Collyridianism) in a theological language similar to that of Eastern Christian writers, some of whom are saints, also introduces new potential ways in which Christians can benefit from engaging with the Muslim scripture. For instance, some Christians may choose to meditate on Qurʾanic passages criticizing the belief in three gods in order to deepen their own understanding of and reverence for the monotheist nature of orthodox Trinitarian doctrine. In this way, they may also come to see the Qurʾan as less antithetical to their own Christian beliefs than they may have assumed. Furthermore, a rejection of the notion that the Qurʾan portrays orthodox belief in the Trinity as polytheism may motivate some Muslims to reevaluate the Christian doctrine in a more charitable light. All of this would greatly benefit Muslim-Christian relations, as it would encourage them to see each other more clearly as fellow believers in the one God of Abraham, Jesus, and Muhammad.