Holy Foolishness in Eastern Orthodoxy and Sufism

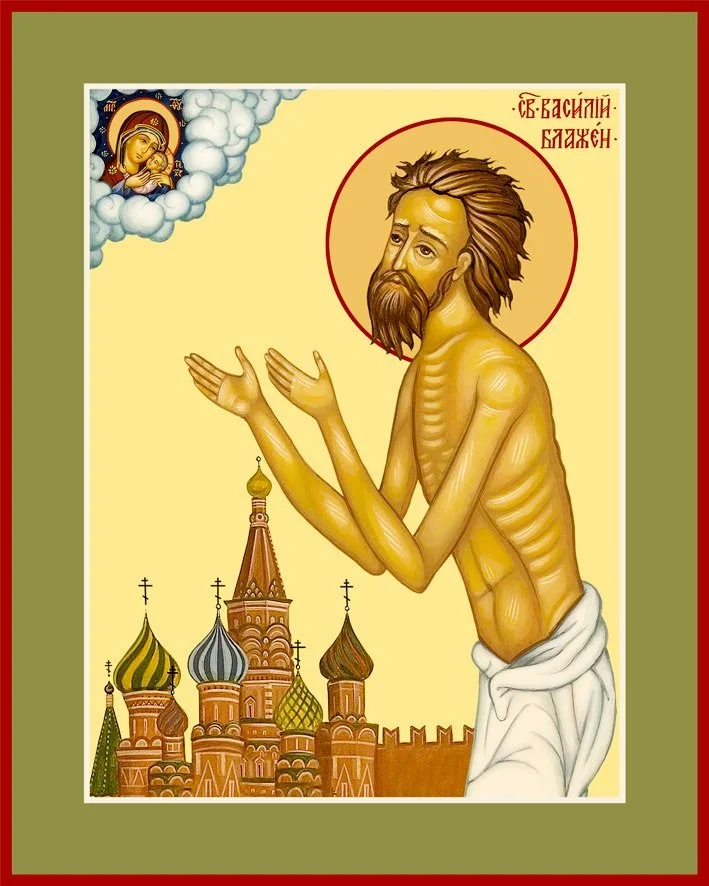

Russian Orthodox icon of St. Vasilii the Blessed of Moscow (Image credit: Казанский кафедральный собор Сызрань)

Foolishness for the sake of God is certainly one of the more eccentric practices found in both Eastern Orthodox Christianity and Sufi Islam. Its practitioner, known aptly as the “holy fool,” often purposely makes themselves appear insane or impious through their flagrant flouting of religious laws and social mores. Yet, they do this not out of a lack of faith or due to a disdain for other people, but because they comprehend God and his creation on a deeper level. In The Orthodox Way, Metropolitan Kallistos Ware writes, “From a practical point of view, no useful purpose is served by anything that the fool does. And yet, through some startling action or enigmatic word, often deliberately provocative and shocking, he awakens men from complacency and pharisaism.” In this way, the fool challenges the sort of legalism, ritualism, and superstition that so often prevents people from coming to truly know God or themselves.

The practice of employing folly as a didactic tool can be found among some of the great prophets of the Old Testament, who at times proclaimed the word of the Lord through shocking and almost enigmatic acts. For instance, Isaiah walked around Jerusalem naked for three years (Isa. 20:2-3), Jeremiah wore the yoke of an ox around his neck (Jer. 27:2), and Ezekiel was commanded by God to publicly bake his bread on human dung (Ezek. 4:12). All of these strange and seemingly foolish examples contained within them divine messages and spiritual lessons that would have likely been less impactful if proclaimed by more conventional means.

The eighth-century Sufi mystic Rabiʿa al-ʿAdawiyya behaved at times in a manner akin to that of the Hebrew prophets. For instance, in order to illustrate her belief that one should worship God without hope of gain, she walked through the streets of Baghdad carrying a bucket of water in one hand and a flaming torch in the other. When questioned about it, Rabiʿa replied, "I want to quench the fires of hell with the water and burn down paradise with the torch, so that people can come to love God selflessly, neither out of fear of the one nor out of greed for the other." For the Sufi saint, the message of selfless faith was far too critical to be proclaimed in a “rational” manner.

Some of the fools mocked the mores of society by their shocking manner of dress, or, like Isaiah, lack thereof. St. Vasilii the Blessed, the eponymous patron of St. Basil’s Cathedral, would often walk through the streets of Moscow naked and in heavy chains. Similarly, some of the Sufi Qalandars also shunned clothing for chains. While another group of Muslim mystics, the Malamatis, would not only opt to go about naked in public but shaved their hair, including their eyebrows, as well. According to Kathryn Babayan in Mystics, Monarchs, and Messiahs, the Malamatis, whose name means “The Blameworthy,” did this as a way to avoid any sort of human praise for their piety.

While we read of the public nudity of some male fools, I cannot say that I am familiar with any accounts of female fools behaving likewise. Yet, there were those who dressed in unconventional ways. An example perhaps particularly relevant to our own time is that of St. Ksenia of St. Petersburg, who famously defied the gender norms of Tsarist Russia. After her husband died suddenly at a party without the benefit of either confession or communion, the twenty-six-year-old Ksenia sought to atone for his immortal soul. Not only did she give away her home and possessions in order take up the life of a wandering fool-for-Christ, but she gave up something far more precious, her very identity. For Ksenia would don her departed husband’s military uniform and refuse to answer to any name but his, Andrei Fedorovich. Unsurprisingly, her crossdressing and rejection of material wealth generated its fair share of anger and mockery among the ignorant of St. Petersburg—much like it would today in many parts of the world. But for those with spiritual eyes, Ksenia had become a living embodiment of Jesus’s words in John 15:13, since she had lovingly laid down her life for someone else.

In The Freedom of Morality, Christos Giannaras argues that the fool’s example “is the incarnation of the Gospel’s fundamental message: that it is possible for someone to keep the whole of the Law without managing to free himself from his biological and psychological ego.” Of course, such a statement is not only relevant to Eastern Orthodoxy but to nearly every religious tradition, including Islam. Thus, some Sufis broke religious laws in an attempt to go beyond the surface level of faith. For instance, we read in Essential Sufism about a particular sheikh who was so impressed by the wisdom of the Persian poet Shams-i Tabrizi that he asked to become his disciple. However, in order to test the man, Shams requested that he fetch them a pitcher of wine to drink together in the Baghdad market. But the sheikh is said to have refused to do so out of fear of public opinion, since the consumption of alcohol is considered haram (forbidden) in Islam. In response, Shams rebuked him: “You are too timid for me. You haven’t the strength to be among the intimate friends of God. I seek only those who know how to reach the Truth.” In seems that in the Sufi master’s eyes, the sheikh had failed to demonstrate a willingness to overcome his ego.

Similarly, the Christian monk St. Symeon of Emesa, who had spent nearly thirty years as an anchorite in the desert before returning to society with the goal of saving others, would publicly break the fasts of the Church in the most scandalous of ways. According to St. Leontius of Neapolis, on some Sunday mornings, Symeon would drape a string of sausages around his torso in the style of a deacon’s stole. He would then walk around the city, dipping them in mustard and eating them from morning on. This was scandalous not only because monastics were forbidden to consume meat, but also because Christians abstained from all food and drink on Sunday morning in preparation to receive the eucharist. Yet, while Symeon appeared publicly as an impious glutton, in private he would fast stricter than most. In this way, the saint not only avoided human praise for his asceticism but was also able to reveal the hypocrisy of those judged him, for they had failed to keep the spirit of the fast.

In The Garden of Truth, Seyyed Hossein Nasr recounts the story of a Malamati mystic who took a similar approach to that of Symeon. During salat al-jumuʿa, or the Friday congregational prayer, the Sufi laid down in front of a mosque and pretended to sleep. However, a self-righteous merchant on his way into the mosque kicked and berated the Malamati for sleeping during a time designated for prayer. But the fool simply shut his eyes, turned over, and feigned going back to sleep. Yet, when the prayers had concluded, the Malamati confronted the merchant outside of the mosque: “While you were outwardly standing in the line of worshippers and making the various movements of the prayers, inwardly your thoughts were completely engrossed in your business affairs and not concerned with God at all, whereas although I was lying down here with my eyes closed, I was thinking only of God.” The man was humbled and repented.

St. Nikolai Salos confronts Tsar Ivan the Terrible by Andrei Ryabushkin (Image credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Some of the fools also used their calling to speak truth to power in ways that few “sane” people would ever dare. For example, the aforementioned Vasilii once reprimanded the Russian tsar Ivan the Terrible for being preoccupied with worldly thoughts while in church. Moreover, another Russian fool, St. Nikolai Salos, would challenge the same tsar for his crimes against humanity. It is said that after massacring thousands of innocent people in Novgorod, Ivan entered the city of Pskov during Lent with a plan to do the same to its population. However, he was soon met by Nikolai, who offered the tsar a hunk of meat dripping with blood. Ivan recoiled at the sight and sanctimoniously said, “I am a Christian and do not eat meat during Lent.” “Yet,” replied the fool, “You drink human blood.” It is believed that Nikolai’s rebuke had such an impact on the tsar that he soon departed from Pskov, leaving it unharmed.

It is also recounted in Essential Sufism how Bahlul the Wise Fool once sat on the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rasid’s throne—a major crime in the caliphate. In response, the palace guard seized him and began to beat him mercilessly. Hearing Bahlul’s cries, the caliph ran to his rescue and scolded his men for harming an “insane” person. Yet, the fool informed Harun that it was not over his own suffering that he cried: “O Caliph! I sat on your throne once, and what a beating I got for sitting there for just a few moments. But you, you have occupied this throne for twenty years. What kind of beating will you be in for, I wonder? It is that thought that has me weeping.” Harun asked him what he should do, to which Bahlul ran off yelling, “Justice, justice!”

That the fools of Islam and Eastern Orthodoxy share much in common with each other is in no small part due to the importance that rules and rituals—e.g., prescribed prayers and periods of fasting—play in the religious life of their respective followers. However, an overemphasis of laws or external acts can cause a spiritual imbalance within a person or community, for it can produce people in the spirit of the scribes and pharisees whom Jesus called hypocrites and likened to “whitewashed tombs” (Matt 23:27-8). Herein enters the fool. For while the fool, if they are an orthodox believer, accepts the dogmas and fundamental observances of their respective tradition, they demonstrate that these things are not to become ends in themselves, and that the one who keeps them without possessing love and humility accomplishes nothing. Thus, the fool may be said to be the Lord’s gadfly, who, through provocative words and outlandish behaviour, reminds humanity to take God to heart and itself less seriously.