Rabiʿa al-ʿAdawiyya’s Radical Love for God and the Orthodox Christian Tradition

Watercolour painting of Rabiʿa al-ʿAdawiyya (Image credit: Nida Naushad’s blog)

I remember years ago stumbling upon an astonishing quote from the eighth-century Sufi mystic Rabiʿa al-ʿAdawiyya, also known as Rabiʿa of Basra:

O my Lord,

if I worship you

from fear of hell, burn me in hell.

If I worship you

from hope of Paradise, bar me from its gates.

But if I worship you

for yourself alone, grant me then the beauty of your Face.

At the time, I was still in high school and finding my way in faith, and I could not really make sense of her words. They sounded almost brazen to me, for had not God according to both the Qurʾan and the Bible told us of Heaven and hell in order to instill in us a desire for the one and a fear of the other? Yet, here was this Muslim mystic seemingly disregarding God’s will.

In fact, Rabiʿa was not just satisfied with the message of forgetting about the rewards of Paradise or the fear of hell being expressed in mere words, she decided to illustrate it in an unforgettable way: she walked through the streets of Baghdad holding a bucket of water and a flaming torch. When questioned about her eccentric behaviour, Rabiʿa replied, "I want to quench the fires of hell with the water and burn down paradise with the torch, so that people can come to love God selflessly, neither out of fear of the one nor out of greed for the other." But how could she want to destroy that which God uses to either inspire or scare humanity into doing what is right? Interestingly, as I learned more about my own Eastern Orthodox tradition, the answer became clearer.

We read in the Book of Proverbs—traditionally attributed to Solomon— “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom” (9:10). While the fear of God has its use, as it helps set a person on the path towards him, the scripture calls it the beginning for a reason, and we never want to end where we started. St. Anthony the Great demonstrates this when he says, "I no longer fear God, but I love Him. For love casts out fear." These words testify to how the father of monasticism had taken 1 John 4:18 to heart and was now living in God’s perfect love.

I also saw parallels between Rabiʿa’s teaching in the eschatology of St. Isaac the Syrian. It is worth noting that there is even an Iraqi connection between Rabiʿa and Isaac, as he had briefly served as bishop of Nineveh (located in modern-day Iraq) and later reposed there less than two decades before Rabiʿa’s birth. In terms of Isaac’s eschatology, he was a universalist. He believed that in the end, God’s desire to reconcile humankind with himself would be fulfilled, and all would be saved. This does not, however, mean that Isaac did not believe in hell. Yet, he did not believe hell to be a geographical place full of literal fire and dancing demons poking at you with pitchforks. Instead, Isaac believed hell, or more precisely Gehenna, to be the temporary spiritual state experienced by a minority of human beings because of their complete rejection of God’s love. But because God is love, even those in hell are not deprived of his love, yet because of their hard-heartedness, it is experienced as akin to burning flames. Thankfully, in the end, all will move towards God, repent, and joyfully reciprocate his endless love.

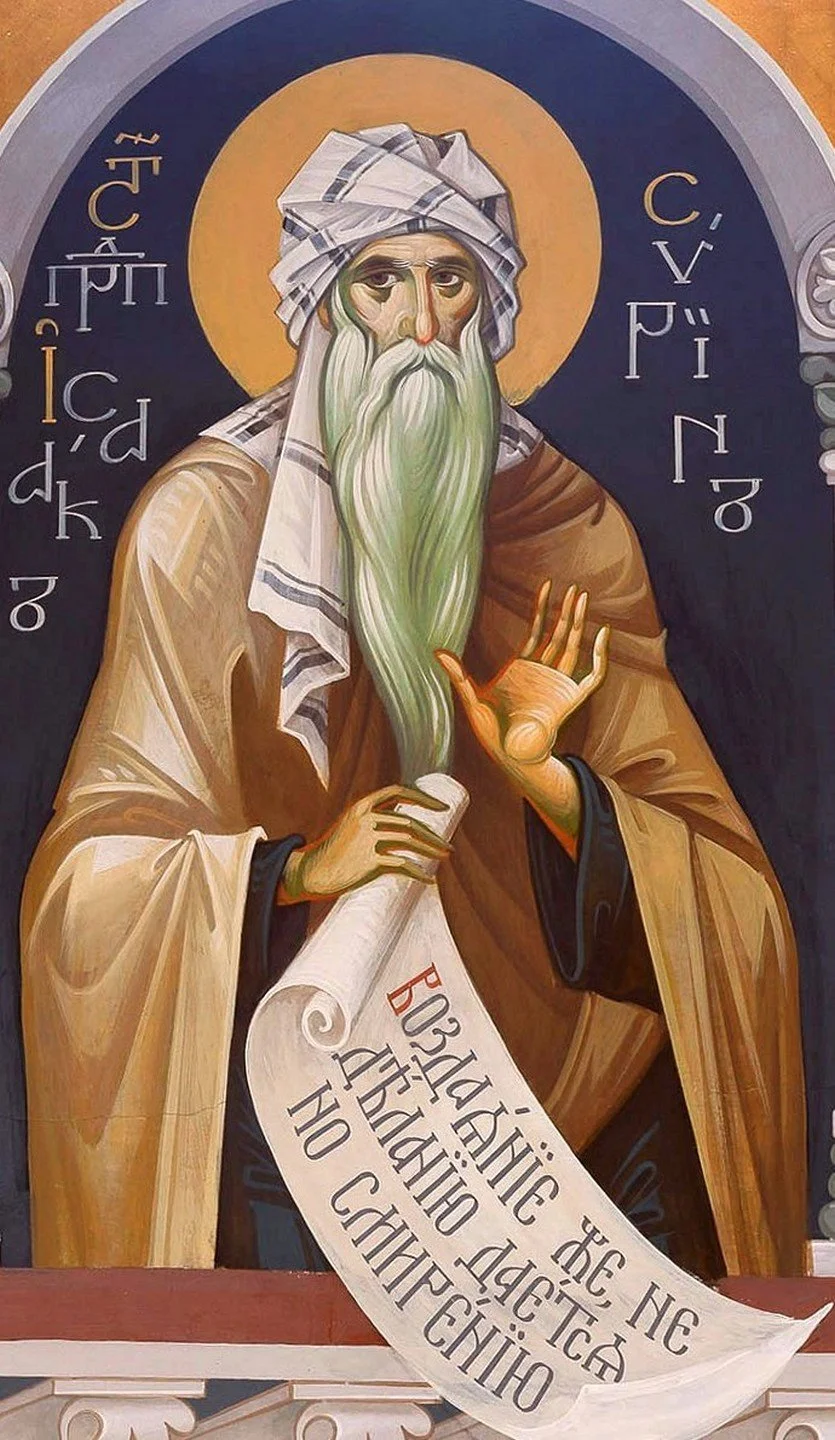

Russian Orthodox icon of St. Isaac the Syrian (Image credit: diomedes2)

Isaac’s eschatological perspective, however, did not cause him to become careless in his religious observances. In fact, Isaac, Anthony, and Rabiʿa all devoted their lives completely to God. Anthony and Isaac were prolific monks who had no interest in worldly pleasures. While the ascetical Rabiʿa, in a move that is relatively abnormal in Islam, chose the path of celibacy, refusing the hand of many a disappointed suitor, for God was her true and only beloved. For these three spiritual giants, the driving force behind their worship of God was not a fear of punishment nor a desire for reward, but pure, unadulterated love for God himself, which was manifested in a desire to know him in this world and in the next.

Further, because the Islamic view of Paradise is often mischaracterized as purely carnal, it is worth noting that Rabiʿa’s profound love for God above all desires is not unique among Muslims. For instance, the Prophet Muhammad’s grandson Husayn ibn ʿAli, who himself would choose to be martyred on the plains of Karbala, Iraq rather than to submit to injustice, is quoted as saying, “There are those who worship God only in fear [of hell], and that is the worship of slaves; there are those who worship God in covetousness [of Paradise] and that is the worship of merchants; but there are those who worship God in thankfulness and this is the worship of free men; it is the best of worship.”

As I learned and grew in my own faith, it not only became clear to me that Rabiʿa’s words were the opposite of brazen, since they showed a true trust in God, but that her words were something that I as an Orthodox Christian needed to take to heart. For Rabiʿa had gone beyond the exteriors of religion, right to the very essence of faith: the love of God. While Rabiʿa’s words had shocked me many years ago, they ended up helping to guide me and give me a fuller understanding of my own tradition. I saw Rabiʿa’s selfless love for God reflected in the words of Anthony and the eschatology of Isaac. Moreover, seeing the parallels between the Sufi mystic’s perspective and that of the Prophet Muhammad’s own grandson also helped me to understand that Rabia’s love was not some anomaly in Islam, but instead represents the spiritual heart of it, just like the teachings of Anthony and Isaac represent the same for Orthodoxy. Lastly, Rabiʿa’s example continues to be a strong reminder for me that we can often come to a deeper understanding of our own tradition when we journey in faith outside of it.